Photo Maike Hickson, St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome

Note from the editor:

The recent unjust action of Bishop Martin in Charlotte, North Carolina, has once more aroused indignation and anguish among many Catholics in the world.

We are pleased to publish a heart-felt and carefully written essay by Father Hansen, a traditional priest, who is discussing here the agony of soul of traditional Catholics, priests and laymen alike, and what their response to the current attack on the traditional Latin Mass and sacraments could be. His reflections should give every bishop in the world, and especially the Pope, reason to reflect on the harm that has been done to innumerable souls. But as long as this persecution has not ended, we need to take prudent steps for the salvation of our souls, and especially that of the children entrusted to us parents by God Almighty.

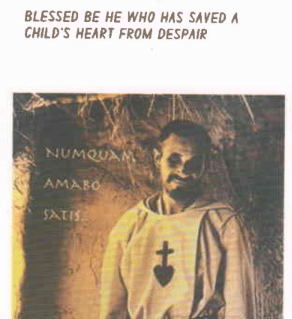

Hansen, who is not a member of the Society of St. Pius X (SSPX) , believes that many traditional priests in today’s crisis can find inspiration in Archbishop Lefebvre’s life and work. His history, so this priest says, can help us get through this liturgical battle that is raging in the Catholic Church right now. He calls Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, the founder of the SSPX, “arguably the greatest servant of Holy Mother Church in the latter half of the twentieth century.”

With regard to “the officially approved traditional priestly institutes, such as the Institute of Christ the King, the Institute of the Good Shepherd, or the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter,” the author finds also words of appreciation: “For the moment, they are operating more or less, but not entirely, unmolested within the ecclesial structures. They have accomplished tremendous good for many souls in need.”

This American priest additionally presents a careful and cautious reflection on those priests who are canceled by an unjust hierarchy and on what they could do, and whether faithful in need of the traditional sacraments may have recourse to such priests. While I myself as a laywoman am not competent in this matter, I hope Father Hansen’s thoughts will encourage further discussions about it.

Moreover, Father Hansen – who writes here under a pseudonym, for understandable reasons – generally wants to express his gratitude to all traditional priests who fight the good fight for the preservation of the traditional Latin liturgy and the traditional faith at large. He insists that their battle is justified, since “it is a question of legitimate self-preservation and self-defense in the supernatural life of faith and grace against the assaults of unjust aggressors, be they ecclesiastical authorities or not.” And he goes on to say that “Catholics are entitled to the life-blood of their souls, namely, the Church’s traditional ministrations, not least of which are the preaching of limpid Catholic doctrine and the administration of the traditional sacramental rites.” As a mother, I whole-heartedly agree with Father Hansen here: for the salvation of the souls of my children, I only want the best that the Church can offer, starting with the traditional rite of Baptism that has several exorcisms attached to it.

Independent of where we stand in the middle of this crisis, however, this good priest reminds us that it is our duty “to live our Catholic lives faithful to the Gospel, true to Jesus Christ and His Church, no matter our rank or condition, according to the means God’s Providence supplies.” With great magnanimity, Father Hansen discusses the crucial question: “How will we fulfill our fundamental and irrevocable baptismal obligation to live a faithful and fruitful Catholic life?” “Each of us,” he states, “will arrive at an answer tailored to his particular circumstances and conformed to God’s will as best he understands it. In the absence of ecclesiastical superiors wielding their authority over us in a faithful manner, we can expect nothing more and nothing less in this time of chaos and infidelity in the Church.”

We thank Father Hansen for sending us this thoughtful essay for publication.

Maike Hickson

Please see here the full text:

In his book, Open Letter to Confused Catholics, Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre stated succinctly the fundamental reality facing faithful Catholics since the close of the Second Vatican Council. “The crisis,” he writes, “is profound, cleverly organized and directed, and by this token one can truly believe that the master mind is not a man but Satan himself. For it is a master-stroke of Satan to get Catholics to disobey the whole of Tradition in the name of obedience.” (chapter 18, “True and False Obedience”)

Those words have aged well. They still ring true, even more profoundly so in the last several years of our own lived experience in the Church. How are Catholics to respond to the ongoing crisis in the Church, especially the persecution of faithful clergy, religious and laity? This is the burning question weighing on the minds and hearts of serious Catholics wishing to remain loyal sons and daughters of Holy Mother Church.

The woes presently afflicting the Church—reaching back many decades—increasingly urge Catholics to find ways to remain faithful while suffering unjust assaults against their spiritual welfare at the hands of ecclesiastical superiors. This has led an increasing number of Catholics to examine marginalized priests or groups of priests who are in effect isolated or quarantined from the mainstream Church as though they were institutional lepers of sorts. These would include those worthy priests unjustly restricted in their priestly ministry due simply to their adherence to Catholic tradition but who could, were it not for their “cancellation” by their superiors acting solely from an anti-tradition animus, come to the aid of Catholics in serious need for the sake of persevering in the bimillenial tradition of Catholic life.

Among such priests or groups of priests, the most prominent and widespread organization is the Priestly Fraternity of St. Pius X. This clerical society of apostolic life is among the oldest and best known organized upholders of integral Catholicism, and is commonly referred to as the Society of St. Pius X, or SSPX, in English-speaking circles.

Increasing numbers of Catholics are moved to seriously examine the life, thought and labors of the Society’s venerable founder, Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, arguably the greatest servant of Holy Mother Church in the latter half of the twentieth century.

The actions of Archbishop Lefebvre and his Society of St. Pius X have always addressed concrete ecclesial problems, not mere theoretical or hypothetical circumstances. This eminently practical approach—authentically pastoral—attracts us because we need practical solutions to the difficulties of daily Catholic living in a prolonged period of crisis, confusion and persecution. This is not to suggest that Lefebvre and his Society left aside doctrinal controversies engendered by the failed Second Vatican Council as secondary or unimportant. Quite the contrary.

Some see Vatican II in its contents, its subversion by the Church’s enemies and its disastrous aftermath as sufficient proof that it was not a work of the Roman Catholic Church, not withstanding the apparent legitimacy of its convocation. While Lefebvre’s criticisms of the Council may not have been that sweeping or severe by comparison, his grasp of the fundamental disease debilitating the minds of modern clerics was firm. He saw that the rejection of the irreformable and perennial Roman magisterium by modern ecclesiastics was the insidious enemy undermining Catholic life. Nevertheless, doctrinal battles did not prevent him from coming to the effective aid of suffering Catholics. He backed his words with concrete actions for their spiritual survival and edification.

We may justifiably suggest that Archbishop Lefebvre’s practical approach arose from his well-known esteem for Aquinas and that same Angelic Doctor’s solid grounding in the theology of what is rather than speculative excursions into what might be. Practical, prudent and effective solutions are needed to meet the needs of beleaguered Catholics who have been abandoned or even attacked by their own spiritual shepherds in their rightful claim to their baptismal heritage. It is a question of legitimate self-preservation and self-defense in the supernatural life of faith and grace against the assaults of unjust aggressors, be they ecclesiastical authorities or not.

Catholics are entitled to the life-blood of their souls, namely, the Church’s traditional ministrations, not least of which are the preaching of limpid Catholic doctrine and the administration of the traditional sacramental rites. Whatever else one may think of Lefebvre, his arguments and his approach to the crisis in the Church, this was his supernatural focus and priestly motivation. No wonder countless Catholics have looked up to this great man of the Church and his priestly society. He proved himself a faithful and trustworthy father and shepherd of souls. No wonder many today are newly learning to cherish this man of blessed memory and are opening their eyes and checkbooks to the SSPX, much to the chagrin of flailing and failing prelates.

Although serious Catholics generally agree in their recognition of the malaise afflicting the Roman Catholic Church these past sixty years, not all will agree on the same practical approach to living our Catholic Faith in this time of crisis. Yet live our Faith we must. It is a crisis situation to which no one can provide a completely satisfying solution. Theological explanations of the crisis seem inadequate. Nor does theology seem to provide us a clear and obvious way forward. Just look at the competing arguments and approaches among traditional Catholics! One thing remains certain, however: we Catholics are still bound to live our Catholic lives faithful to the Gospel, true to Jesus Christ and His Church, no matter our rank or condition, according to the means God’s Providence supplies.

In view of the desperate need for Catholics to survive, voices are calling out for solutions that enable Catholics to operate in such a way that they might tap into the ministrations of faithful, but marginalized priests while avoiding corrupting influences presently endangering, threatening or undermining their Catholic lives.

While the SSPX provides spiritual sustenance for many Catholics, not all can avail themselves of what the Society has to offer. It is also unlikely that the SSPX has the human and material resources needed by marginalized Catholics simply wishing to faithfully carry on their Catholic lives in a manner pleasing to God.

What about relying on the officially approved traditional priestly institutes, such as the Institute of Christ the King, the Institute of the Good Shepherd, or the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter? For the moment, they are operating more or less, but not entirely, unmolested within the ecclesial structures. They have accomplished tremendous good for many souls in need. The good work each organization does for the Church and souls is evident, even if some might not accept, at least in the case of the Fraternity of St. Peter, the rationale for its founding in the heady days following the consecration of four SSPX priests to the episcopate by Archbishop Lefebvre and Bishop Antonio de Castro Mayer on June 30th, 1988.

The rationale of the Fraternity of St. Peter’s founders was that they did not wish to follow Lefebvre and his Society into supposed schism and excommunication from the Church. A more complete and honest reading of the 1983 Code of Canon Law, however, would seem to militate against their severe judgment and that of Pope John Paul II (in Ecclesia Dei adflicta) and Cardinal Gantin, whose Congregation for Bishops publicly declared the automatic excommunication of Lefebvre, de Castro Mayer and the four freshly-minted bishops.

In addition to this, the actions of the popes in more recent years, including the official lifting of the excommunications against the four living bishops in 2009, would indicate that the SSPX is in no way outside the Church. Rather, the SSPX, appealing to higher principles, which inform the particular laws of the Church, is simply operating outside the usual canonical norms for grave reasons regarding the salvation of souls.

Unfortunately, we have already seen the heavy hand of persecution strike approved priestly institutes in some locations. They remain beholden to diocesan and Roman dictates and, to that extent, their continued existence and apostolic work hang in the balance.

Furthermore, the practical submission of these officially approved groups to a corrupt system risks stifling their freedom of preaching and action. Beyond this, their material and moral proximity to the systemic corruption in its many and varied manifestations prevailing in the existential Church since the close of Vatican II is often problematic and burdensome to the consciences of not a few Catholics, not withstanding the valid moral arguments proffered in defense of these institutes. Suffice it to say that the priests of these institutes and the faithful who resort to them see their cooperation with Church authorities and structures as an unavoidable and morally defensible position made necessary to remain under the lawful authorities established by Christ for our salvation. They might say that this is as unavoidable and necessary as paying taxes to wasteful and corrupt government entities.

One may argue that submitting to lawful Church authorities and supporting their programs and structures is necessary, come what may, even if what has come our way is an unprecedented corruption and malfeasance wrought by the very authorities who should use their position and power to feed their sheep and lead them to Heaven, but are often doing just the opposite. However, such an argument seems to defy common and Catholic sense. We do not live in a textbook-perfect Church, where all things are normal and the authorities fulfill their responsibilities for the good of souls and the advancement of the interests of God. The waywardness of the Church’s pastors makes it necessary for many of us to consider seeking out non-textbook solutions to remaining Catholic in the Church while having to avoid destructive and dangerous elements in the system, so to speak.

The flesh-and-blood reality of Catholic life today is not that of a disincarnate theology and a fanciful imagination feverishly desiring things to be other than they are. No. The reality put before us, clergy and laity alike, is a moral choice unlike any other in Church history in its ubiquity and gravity: Do we maintain the Faith and the life of grace, or must we expose them to peril by submitting to the dangerous and unjust dictates of a nearly universally abusive authority?

Amidst the spiraling degradation in the world and in the Church in its human element, we ask ourselves how we can respond. How will we fulfill our fundamental and irrevocable baptismal obligation to live a faithful and fruitful Catholic life? Each one of us will have to arrive at an answer tailored to his particular circumstances and conformed to God’s will as best he understands it. Wherever and whenever we are confronted by the unfortunate, but unavoidable absence of ecclesiastical superiors wielding their authority over us in a faithful manner, we can expect to make difficult and often painful practical decisions contrary to the dictates of these same authorities. Our forebears in the Faith had to do the same in times of persecution, even when the persecutors were Christ’s unfaithful ministers. These heroes often paid a heavy personal price. Sacrifice and fidelity to Christ and His Church go hand in hand.

Many feel that the problems in the world and the Church are beyond our purview or ability to solve. What then? John Henry Newman declared: “Saints are lowered that the world may rise.” Personal holiness lifts up the world around us. Its fervent and humbling pursuit is our baptismal calling and within our reach, or God would never have called us to it nor expect it of us. As Dom Chautard tells us in his magnificent masterpiece, The Soul of the Apostolate, personal holiness is the indispensable foundation of any pursuit designed to lift souls from ruin and place them on the path to eternal salvation.

Is not this salvation what we desire for ourselves and others? Every Catholic worthy of the name ardently desires this. We know the pursuit of holiness can and must be our first and immediate response to the current troubles, and, God knows, it may very well prove the unique antidote to all that ails us.

This truth is very reassuring. It guards us from temptations to frustration, discouragement and despair. By pursuing holiness, we are pushing back the tide of evil. We are putting at bay certain evils that would otherwise influence us and those for whom we have responsibility. We are thereby already engaged in some heavy spiritual lifting. The world already begins to rise.

Some among us may be called to do more, to engage in external works which directly confront the evils of our day, and seek to assuage them, replacing them with concrete good works beneficial to the common good and the welfare of souls. These are the men and women called beyond the confines of private life and the personal building up of the kingdom of God to engage in public works for God’s glory and the salvation of souls. We might call them apostles of sorts, or public champions for the cause of God and Holy Church.

What about clerics? What is their vocation? Clerics are called to publicly build up the Church according to their rank and responsibilities. The sacrament of Holy Orders is aimed at the public good of the Church. It is not primarily for the personal and private good of the cleric, but rather for the good of the faithful, the building up of the Mystical Body of Christ. Moreover, the personal holiness of the priest, living in the world without the three vows of evangelical perfection, is attained particularly through the exercise of his priesthood in the pastoral care of souls.

What cannot be forgotten, however, by both laity and clergy, is the principle that “a priest is nothing without his bishop,” or lawful ecclesiastical superior. The nature of the priesthood is such that a priest cannot normally function in the Church without being sent by the Church to take care of souls. In other words, the priest must have a lawful mission, a canonical mission, a mission according to the norms of ecclesiastical law. “As the Father hath sent me,” Jesus tells His apostles, “I also send you” (Jn. 20:21). “Going, therefore, teach ye all nations: baptizing them . . .” (Matt. 28:19). “And how shall they preach unless they be sent . . .” (Rom. 10:15). And if bishops and superiors do not send their own worthy priests who are ordained to serve the serious needs of the faithful in a time of general institutional collapse, what then?

In light of this reality, such clerics face an obvious dilemma, similar to that faced by the faithful. They must carefully discern the will of God and prudently pursue it. They must be wise as serpents and simple as doves, just as Our Lord has commanded. Though often deprived or attacked by their superiors, they must faithfully fulfill their baptismal and priestly vocations and at the same time remain in the Church in union with all who adhere to the Apostolic Faith. They, like all Catholics, must cling to “one Lord, one faith, one baptism” (Eph. 4:5).

Many priests wrestle with this moral dilemma precisely because they wish to be faithful to the Church and their priestly calling. Suffering spiritual and moral violence at the hands of their superiors, they find themselves faced with a crushing moral quandary: Obey superiors who inflict spiritual harm, or obey the clear demands of the Catholic Faith.

This agonizing choice is all the more present in the lives of priests today who wish to embrace traditional Catholicism in its life-giving fullness, especially since the publication of Traditionis custodes in 2021, which severely curtailed the use and frequency of the traditional Roman liturgical rites. This represented a shocking reversal of Pope Benedict XVI’s “freeing” of the same rites in 2007 (in his Summorum pontificum motu proprio). Many priests who have been celebrating the traditional Roman rites, or who have desired to do so, have suffered and are suffering the arbitrary and unjust dictates of an authority exercised against the good of their souls and the souls of those whom they were ordained to serve.

All of this being stated, we come to the present circumstances facing the clergy and faithful of various dioceses who have felt, or are expecting to soon feel, the heavy hand of bishops who are determined to smother vibrant traditional Catholic life in their domains. Among the most recent in the United States, for instance, is the case of the Diocese of Charlotte, North Carolina. The local ordinary, Bishop Michael T. Martin, OFM, Conv., has decreed the suppression of the celebration of the traditional Roman Rite of Holy Mass by clergy of his diocese in four locations. He expects the Catholic faithful to be sequestered in a non-parish-church venue for a limited celebration of the traditional Latin Mass. In the face of public outcry, however, the diocese officially announced that the date these dictates take effect has been pushed back from July 8th to October 2nd, 2025, the original date given by Rome for the implementation of the provisions of Traditionis custodes.

Should he succeed in implementing these provisions in his diocese, Bishop Martin will be restricting the rights of his subjects which they possess in virtue of their baptism. He will unreasonably increase their burdens and viciously undermine their spiritual good. What are these faithful Catholics to do in response to their bishop’s unjust actions?

Some of the faithful have already organized petitions to the authorities for a redress of their grievances concerning Latin Mass restrictions (cf. lifesitenews.com under the heading of Petitions). Others are leading an effort to file an official canonical appeal to the Roman authorities for a reversal of Bishop Martin’s decree (cf. faithfuladvocate.org). This is commendable, since these faithful are taking the ordinary means at their disposal for a solution.

It is important not to dismiss this approach which relies on the ordinary means the Church’s legal norms and even elementary justice urge. If legitimate ecclesiastical superiors are physically and morally approachable, they should be made aware of the needs of the faithful and be urged to respond as good spiritual shepherds would respond. We see this in Charlotte. Note that we can also look at the history of the post-Vatican II crisis and recognize this prudential approach in the actions of Archbishop Lefebvre over many years in his dealings with the Roman authorities. Lefebvre always insisted that his priests follow the norms of the Church to the extent possible even in a time of prolonged crisis.

Should the good-faith efforts of Catholics in Charlotte and elsewhere fail to achieve a favorable outcome for their spiritual welfare, then extraordinary measures to preserve their spiritual well-being will have to be considered.

We have before us the example of some of our fathers and mothers, grandparents and other Catholics of their generations. See what they did 50 to 60 years ago after the close of Vatican II, when a subversive anti-Catholic revolution and its New Mass were cleverly and even ruthlessly imposed on the Church and her trusting children. These men and women, who sensed in some way the perfidious machinations of the Church’s enemies in their midst, found a way to remain Catholic and to pass down the unblemished Faith to us.

So, here is the present challenge before us, the inescapable burden Divine Providence calls us to carry. Catholics will have to consider doing what their elders did, namely, distance themselves from the abusive actions of their bishops, establish venues for the celebration of the traditional Latin Mass, and find good Catholic priests willing to pay the price for extending their priestly charity to souls in need.

As “in days of old,” years and even decades before 2007’s Summorum pontificum, Catholics today may have to travel long distances to find churches and chapels where the priests faithful to tradition provide for their spiritual needs. They would thereby have recourse to priests who enjoy official approval for their ministry, or even to the SSPX. This option may entail more hardships and less convenience than options formerly provided by diocesan bishops closer to home. Much more time on Sunday may have to be “the Lord’s” than was the case until now. Catholics making sacrifices for the Mass may have to increase them so that they may continue to fittingly and fruitfully give God what is His due through the Sacrifice of the Mass in the venerable Roman Rite.

When these options cannot be had without gravely burdensome efforts, the Catholic faithful seeking to fulfill their legitimate needs will have to look to other priests, namely, those mentioned at the beginning of this writing: “worthy priests unjustly restricted in their priestly ministry due simply to their adherence to Catholic tradition but who could . . . come to the aid of Catholics in serious need . . . .”

We happily see some efforts being made to aid these priests and to give them the opportunity to serve the persecuted faithful. Recourse to such priests is possible given the hardships in which the faithful involuntarily find themselves in nearly all dioceses throughout the world. However, precautions are in order.

These priests may legitimately be asked by the faithful in real spiritual need to provide for them, just as the Good Samaritan cane to the aid of the beaten, half-dead Jew on the side of the road who had been ignored and abandoned by his lawful spiritual “leaders,” the priest and the Levite. In fact, the greater the need and more insistent the appeal of the abandoned faithful, the more such priests can and must do for them. This was and is the very operating principle found in Archbishop Lefebvre and his Society. But note carefully the practical prudence they ordinarily observed.

Vae soli is the Latin phrase meaning “Woe to the one who is alone.” Societies of priests such as the SSPX, the FSSP, the Oratorians and other priestly institutes, have at their core the common life, whereby members share the basic elements of priestly life while living in community with one another. Prayer, meals, recreation and apostolic labors are shared in a greater or lesser degree. This life in common offers its members an internal governing authority, mutual support, encouragement in virtue, fraternal correction, moral discipline and opportunities for curbing the temptations to self-will and the dangerous self-deception too common among men who consider themselves in no need of others.

In light of this prudential approach to priestly life, the faithful will have to exercise careful discernment as they consider availing themselves of these good “canceled” priests. Are these priests actively seeking someone who can act as a kind of ecclesiastical superior, overseer or advisor as a measure of prudence, even if that relationship remains unofficial or non-canonical? It is not advisable to resort to these priests unless they are bound, at least voluntarily, to some mechanism of accountability with a member of the hierarchy or several prudent priests or a solid group of priests such as the SSPX. In fact, the SSPX has traditional priest “Friends of the SSPX” whom it deems worthy to support and recommend to the faithful. A priest who voluntarily distances himself and his activities from such oversight is best avoided.

In addition to this, the faithful will have to discover whether or not these Catholic priests are worthy of their confidence. Are such priests duly formed and ordained? Do they possess a priestly spirit and priestly virtue? Do they conform themselves to the mind and doctrine of the Church? Do they strive to fulfill their duties as best they can in conformity to traditional norms, not withstanding the grave crisis and grievous abnormalities presently afflicting the functioning of the existential Church?

Are such unauthorized priests “forced” to exercise public ministry outside the normal confines of the law? Are they morally justified in operating outside of the law? Were there no ongoing crisis of faith and authority in the Church, the answer would be a simple and unqualified “No.” But we are not living in such times, and we have not been since the unleashing of turmoil, confusion and spiritual dangers since Vatican II.

What is suggested here does not come without peril to the faithful themselves and to the unjustly marginalized priests who might serve their needs. The danger of moral separation from other Catholics, especially by way of elitist or schismatic attitudes, can be found in some individuals and communities. There is also the danger of becoming accustomed to an abnormal relationship with Church authorities as the “new normal” for Catholics, to the extent that these authorities are considered irrelevant or at best optional feature in Catholic life. Such a mindset opens the door to rejecting any future attempts at working with legitimate authorities.

Beyond this normalization of the abnormal, another risk devolves to the priests and faithful which would in saner circumstances ordinarily weigh upon their ecclesiastical superiors. Priests and faithful distancing themselves from the normal and ordinary practical governance of their ecclesiastical superiors, even though justified in doing so based on higher principles, bear an increased responsibility for their salvation and for those under their care.

These risks and dangers are practically inevitable. They are imposed on us because of baneful circumstances not of our making, even though we might wish otherwise. Let us pray for the grace to endure these things unscathed, and let us also face with eyes wide open the unfortunate reality of our present situation in the Church: our shepherds have been struck, “and we like sheep” must wander amidst great and ever-present dangers in order to spiritually “graze” in the verdant life-giving pastures of Christ’s Church.

In sum, it would seem entirely justifiable, according to the norms of the divine law and the higher principles informing canon law concerning the salvation of souls, for the abused and persecuted faithful, deprived by their spiritual fathers of what is rightfully theirs, to have recourse to such priests. Furthermore, the priests who are approached by these persecuted faithful, would seem to have a corresponding obligation to come to their aid. In such extraordinary circumstances, neither the faithful nor the priests could be justly accused of disobedience or rebellion against their bishop. Rather, they would simply be obeying a higher law; they would be directly obeying God Himself. The bishop who is maltreating them, on the other hand, would be abusing his authority, thereby forfeiting any claim in that instance to the obedience of his subjects.

Keenly aware of the challenge before us, fully cognizant of the impact our practical choices for spiritual survival and flourishing have on our sanctification and eternal salvation, let us fervently and perseveringly pray for the light to see what God wants us to do, and the strength to accomplish it. And may the Mother of God guide and protect us as we strive to be faithful children of Christ’s Holy Church.

Fr. Martin Hansen

July 2, 2025

Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Robert Hickson, Jr. Maike Hickson

Robert Hickson, Jr. Maike Hickson